hd Module¶

This module provides functions to estimate covariance matrices in high dimension, i.e., when the concentration ratio is not small or even greater than one.

Functions¶

|

The infeasible finite sample optimal rotation equivariant covariance matrix estimator of Ledoit and Wolf (2018). |

|

Linearly shrink a covariance matrix until a condition number target is reached. |

The linear shrinkage estimator of Ledoit and Wolf (2004). |

|

|

The nonparametric eigenvalue-regularized covariance matrix estimator (NERCOME) of Lam (2016). |

|

The nonparametric eigenvalue-regularized integrated covariance matrix estimator (NERIVE) of Lam and Feng (2018). |

Compute the shrunk sample covariance matrix with the analytic nonlinear shrinkage formula of Ledoit and Wolf (2018). |

|

|

Convert a covariance matrix to a correlation matrix. |

The need for regularization¶

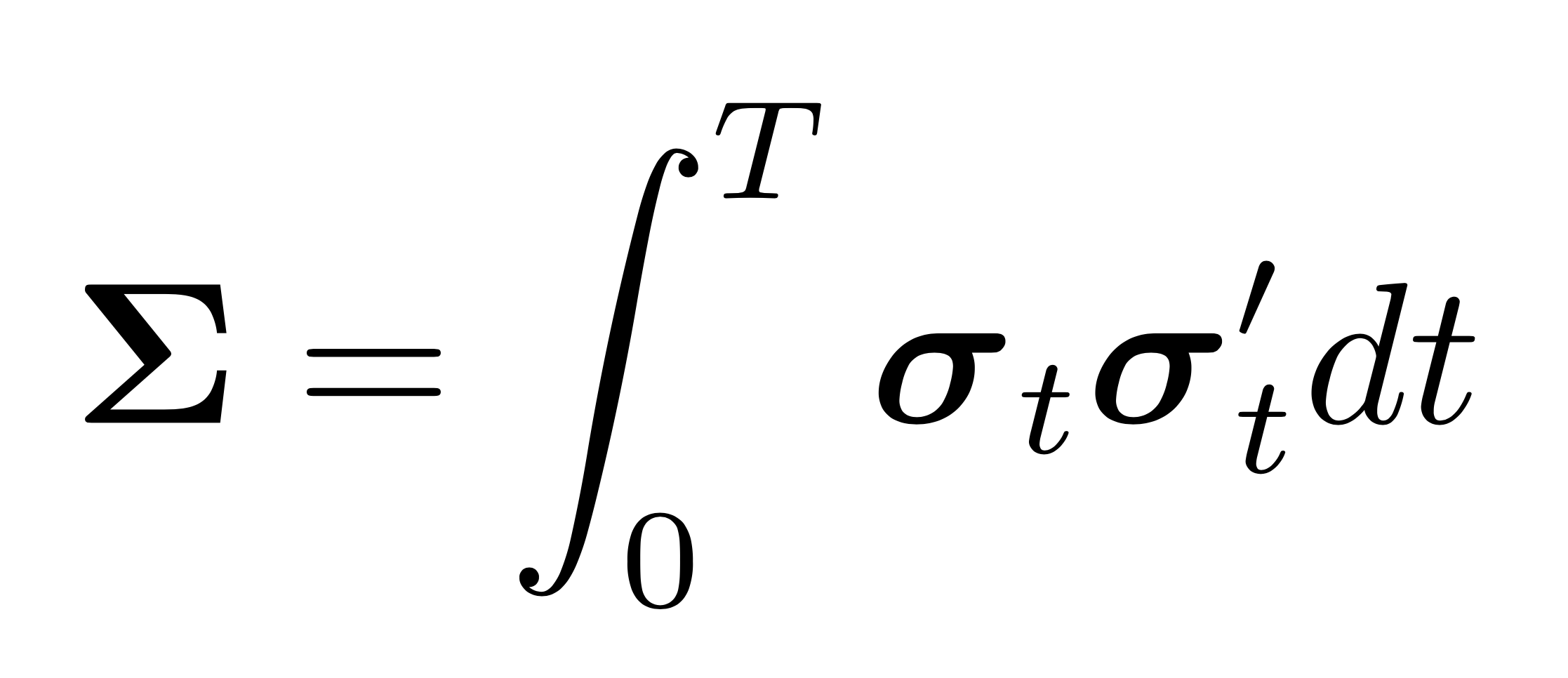

The sample covariance matrix and especially its inverse, the precision matrix, have bad properties in high dimensions, i.e., when the concentration ratio \(c_n = \frac{p}{n} \) is not a small number. Then (1) the sample covariance matrix is estimated with a lot of noise since \(\mathcal{O}(p^2)\) parameters have to be estimated with \(pn = \mathcal{O}(p^2)\) observations, if \(n\) is of the same order of magnitude as \(p\) . And (2), if the first principal component of returns explains a large part of their variance, the condition number of the population covariance matrix, \(\mathbf{\Sigma}\), is already high. A high concentration ratio increases the dispersion of sample eigenvalues above and beyond the dispersion of population eigenvalues, increasing the condition number further and leading to a very ill-conditioned sample covariance matrix.

Mathematically, as illustrated by Engle et al. 2019, the last point can be seen as follows. Define the population and sample spectral distribution, i.e., the cross section cumulative distribution function that returns the proportion of population and sample eigenvalues smaller than \(x\), respectively, as

$$\begin{aligned} &H_{n}(x):=\frac{1}{p} \sum_{i=1}^{p} \mathbf{1}_{\left\{x \leq \tau_{i, T}\right\} } , \forall x \in \mathbb{R}, \ &F_{n}(x):=\frac{1}{p} \sum_{i=1}^{p} \mathbf{1}_{\left\{x \leq \lambda_{i, T}\right\}}, \forall x \in \mathbb{R}. \end{aligned}$$ Under general asymptotics and its standard assumptions, \(p\) is a function of \(n\) and both \(p\) and \(n\) – not just \(n\) – go to infinity. Then, according to Silverstein (1995), $$F_{n}(x) \stackrel{\text { a.s }}{\longrightarrow} F(x), \quad$$ where \(F\) denotes the nonrandom limiting spectral distribution. From the equality \begin{equation} \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} x^{2} d F(x)=\int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} x^{2} d H(x)+c\left[\int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} x d H(x)\right]^{2} \end{equation} it can be seen that if the limiting concentration ratio \(c\) is greater than zero, the sample eigenvalue dispersion is inflated. The mean of the sample eigenvalues, however, is unbiased \begin{equation} \label{eqn: eigenvalue_mean} \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} x d F(x)=\int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} x d H(x). \end{equation}

The distortion of extreme eigenvalues is very large for high concentrations. But even for relatively small \(c\), the eigenvalue dispersion can be high enough such that regularization is necessary to ameliorate instability. The mathematical intuition behind this can be seen from the Marchenko-Pastur, which states that the limiting spectrum of the sample covariance matrix \(\mathbf{S} = \mathbf{X} \mathbf{X}'/n\) of independent and identically distributed \(p\)-dimensional random vectors \(\mathbf{X}=\left(\mathbf{x}_{1}, \ldots, \mathbf{x}_{p}\right)'\) with mean \(\mathbf{0}\) and covariance matrix \(\mathbf{\Sigma}=\sigma^{2} \mathbf{I}_{p}\), has density \begin{equation} f_{c}(x)=\left\{\begin{array}{ll} \frac{1}{2 \pi x c \sigma^{2}} \sqrt{(b-x)(x-a)}, & a \leq x \leq b \ 0, & \text { otherwise, } \end{array}\right. \end{equation} where the smallest and the largest eigenvalues are given by \(a=\sigma^{2}(1-\sqrt{c})^{2}\) and \(b=\sigma^{2}(1+\sqrt{c})^{2}\), respectively, as \(p, n \rightarrow \infty\) with \(p / n \rightarrow c>0\). To illustrate, say the interest lies on estimating a covariance matrix for 1000 stocks on daily data and suppose finite sample behavior of eigenvalues is reasonably well approximated by the Marchenko-Pastur law. Using a rolling window of anything less than approximately 4 years of daily returns results in a singular covariance matrix. Widening the window to include 8 years of data, the concentration ratio would be approximately \(c_n=1/2\). Plugging this number into the equations for the smallest and largest eigenvalues, it can be seen that they are, respectively, 91% smaller and 191% larger than the population eigenvalues, which are equal to \(\sigma^{2}\). Even for an extremely wide window of 40 years, the eigenvalues would still be underestimated by 53% for the smallest, and overestimated by 73% for the largest. To reduce the overdispersion enough such that the covariance matrix becomes well-conditioned, such a wide window would be necessary that inaccuracies due to non-stationarity would dominate, if the data are even available. Empirically, the cross-section of stock returns exhibits correlation, hence \(\mathbf{\Sigma} \neq \sigma^{2} \mathbf{I}_{p}\). Ait-Sahalia and Xiu (2017), for example, find a low rank factor structure plus a sparse industry-clustered covariance matrix of residuals, which may exacerbate the instability of the precision matrix since the eigenvalues of the population covariance matrix are already highly dispersed.

The solution to (1) is to reduce the number of parameters by identifying a small number of factors that explain a large proportion of the variance and then estimating the factor loading of each stock on those factors, which reduces the number of parameters considerably if \(p\) is large. The solution to (2) is to shrink the covariance matrix towards a shrinkage target which has a stable structure such as the identity matrix. This has the effect of pulling eigenvalues of the sample covariance matrix towards their grand mean, which is unbiased, while keeping the sample eigenvectors unaltered. Estimators that retain the original eigenvectors while seeking better properties through modification of the eigenvalues are called rotation equivariant. The result is a reduction of dispersion of sample eigenvalues and thus the condition number. Since overfitting is known to increase the dispersion of sample eigenvalues, shrinking them has the effect of regularization.

Rotation equivariance¶

The literature of eigenstructure regularized covariance estimation for portfolio allocation is predominantly focused on rotation equivariant estimators. To define the estimator consider the sample covariance matrix \(\mathbf{S}_{n}:=\mathbf{X}_{n} \mathbf{X}_{n}' / n\) based on a sample of \(n\) i.i.d. observations \(\mathbf{X}_{n}\) with zero-mean. For the sake of readability, the sample suffix is suppressed in the following text unless it is not clear from the context that the quantity depends on the sample. According to the spectral theorem the sample covariance matrix can be decomposed into \(\mathbf{S}=\mathbf{U}\mathbf{\Lambda} \mathbf{U}^{\prime},\) where \(\mathbf{\Lambda}\) is a diagonal matrix, whose elements are the eigenvalues \(\mathbf{\lambda}=\left(\lambda_{1}, \ldots, \lambda_{p}\right)\) and an orthogonal matrix \(\mathbf{U}\), whose columns \(\left[\mathbf{u}_{1} \ldots \mathbf{u}_{p}\right]\) are the corresponding eigenvectors. A rotation equivariant estimator of the population covariance matrix \(\mathbf{\Sigma}\) is of the form

\begin{equation}

\label{eqn: re}

\widehat{\mathbf{\Sigma}}:=\mathbf{U}\widehat{\mathbf{\Delta}}\mathbf{U}^{\prime}=\sum_{i=1}^{p} \widehat{\delta}_{i} \cdot \mathbf{u}_{ i} \mathbf{u}_{i}^{\prime},

\end{equation}

where \(\widehat{\mathbf{\Delta}}\) is a diagonal matrix with elements \(\widehat{\mathbf{\delta}}\). The infeasible finite-sample optimal rotation equivariant estimator, hd.fsopt(), choses the elements of the diagonal matrix as

\begin{equation}

\label{eqn: optimal re}

\mathbf{d}^{*}:=\left(d_{1}^{*}, \ldots, d_{p}^{*}\right):=\left(\mathbf{u}_{1}^{\prime} \mathbf{\Sigma} \mathbf{u}_{1}, \ldots, \mathbf{u}_{p}^{\prime} \mathbf{\Sigma} \mathbf{u}_{p}\right).

\end{equation}

This estimator is an oracle since it depends on the unobservable population covariance matrix. In order to be feasible, \(\widehat{\mathbf{\Delta}}\) has to be estimated from data. The hd.linear_shrinkage(), and the hd.nonlinear_shrinkage() estimator, estimate the elements of \(\widehat{\mathbf{\Delta}}\), i.e., \(\widehat{\mathbf{\delta}}=\left(\widehat{\delta}_{1}, \ldots, \widehat{\delta}_{p}\right) \in\)

\((0,+\infty)^{p}\), as a function of \(\mathbf{\lambda}_{n}\). These two approaches differ in how many parameters this function takes. They both are elements of the rotation equivariant class, though. Within this framework, originally due to Stein (1986), lecture 4, rotations of the original data are deemed irrelevant for covariance estimation. Hence, the rotation equivariant covariance estimate based on the rotated data equals the rotation of the covariance estimate based on the original data, i.e., \(\widehat{\mathbf{\Sigma}}\left(\mathbf{X} \mathbf{W}\right)=\mathbf{W}^{\prime} \widehat{\mathbf{\Sigma}}\left(\mathbf{X}\right) \mathbf{W}\), where \(\mathbf{W}\) is some \(p\)-dimensional orthogonal matrix. This characteristic distinguishes the class of rotation equivariant estimators from regularization schemes based on sparsity, since a change of basis does generally not preserve the sparse structure of the matrix.

References¶

Ait-Sahalia, Y. and Xiu, D. (2017). Using principal component analysis to estimate a high dimensional factor model with high-frequency data, Journal of Econometrics 201(2): 384–399.

Stein, C. (1986). Lectures on the theory of estimation of many parameters, Journal of Soviet Mathematics 34(1): 1373–1403.

Marchenko, V. A. and Pastur, L. A. (1967). Distribution of eigenvalues for some sets of random matrices, Matematicheskii Sbornik 114(4): 507–536.

Engle, R. F., Ledoit, O. and Wolf, M. (2019). Large dynamic covariance matrices, Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 37(2): 363–375.

Silverstein, J. W. (1995). Strong convergence of the empirical distribution of eigenvalues of large dimen- sional random matrices, Journal of Multivariate Analysis 55(2): 331–339.